Ethereum Macroeconomics

This is the first of two posts on Ethereum macroeconomics.

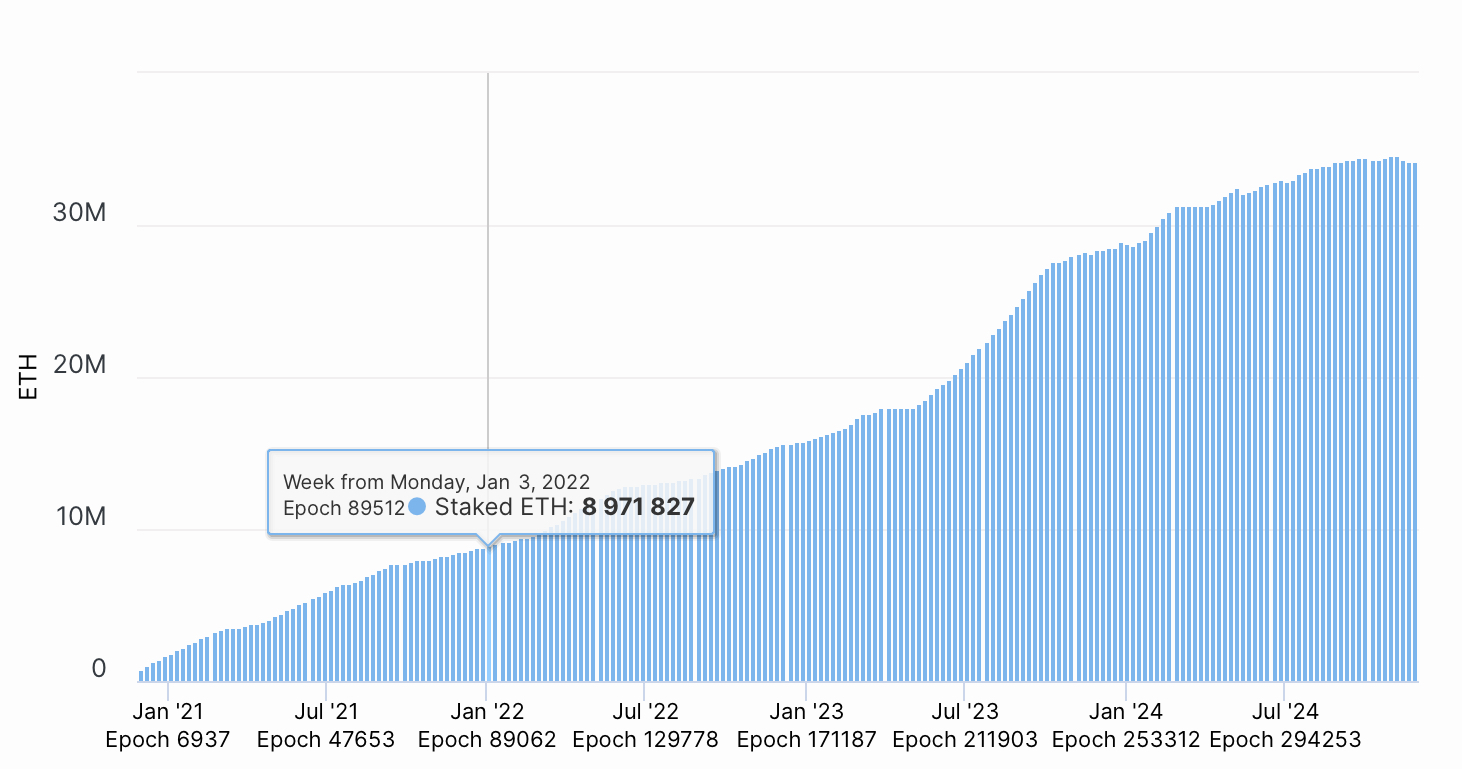

Ethereum has grown into a major economic force; between its native asset Ether (ETH), the smart contract ecosystem this supports, and the Layer-2 blockchains, a conservative valuation might be half a trillion dollars. At the core of Ethereum’s “brand”, distinguishing it from other smart contract platforms, is the consistent effort put into decentralized governance. Via its consensus mechanism no central authority can censor a transaction, freeze the native asset of a user, etc. This brand commitment depends in turn on a sufficient diversity of validators staking ETH to participate in consensus.

The share of Ether staked by “centralized” staking services, such as exchanges and Liquid Staking Providers (LSPs) is considerable, and continues to grow. This has provoked concerns, among Ethereum researchers that the future of Ethereum might involve a confluence of three interrelated challenges

- Nearly all Ether becomes staked.

- Inflation becomes excessive.

- Governance becomes centralized.

upon which we focus. The view of inflation emphasized in this work in particular feels quite different to us, than the views expressed for instance, in this very helpful review podcast.

Lookahead

In this blog post we address the first of these concerns “runaway (near 100%) staking” \(s\to1\) and how it relates to the second, using a “stock and flow” macroeconomics model built with guidance from dynamical system theory. In contrast with other research, we find inflation playing a positive role in moderating runaway staking, but eventually inflation must subside, along with the moderation it provides.

In the second post, we look more closely at governance centralization and discuss a means for evaluating macroeconomic interventions inspired by bifurcation theory. Briefly, we are not optimistic that reducing issuance will prevent governance centralization, either.

In both posts, we provide a few code examples using ethode, a thin units-aware wrapper we built around scipy.integrate.solve_ivp, to streamline model evaluation. Readers desiring to follow our derivations, dive into technical mathematical points not covered here, run their own simulations, or learn some dynamical systems are recommended to look at our ethode guide, which contains References section below. The guide is certainly a work in progress, but should have enough to get you going.

For The Impatient!

Issuance does not all get dumped into native unstaked Ether. Some portion of it is reinvested by staking businesses at ratio $r$; indeed this process is coded into Liquid Staking Token (LST) smart contracts. It is important to distinguish between transient behavior, such as speculation in staking, and medium/long-term behavior, such as the reinvestment of staking rewards by staking businesses. When staking is dominated by reinvestment instead of speculation, inflation persistently decreases.

We use our macroeconomics model to identify a friend “Mr.LI;ELF”: “Medium $r$. Low Inflation; Even Lower Fees”. Without Mr.LI;ELF convergence to a desirable future without runaway staking is unlikely. Strong deflation, in which the magnitude of deflation exceeds the reinvestment of transaction fees, probably corresponds to unstable dynamics. Under zero or weak deflation, the tendency toward runaway staking can be moderated only by high churn and/or slashing.

In contrast with Mr.LI;ELF staked ETH fraction approaches to a value above moderate reinvestment ratio $r$. How far above depends on the “ELF” part. Thus, runaway staking can be avoided only while inflation is held

-

low enough, that concerns over inflation do not dominate the reinvestment of profits by staking businesses at equilibrium, \(\left(\frac{dr}{d\alpha}\right)^\star<0\) (no news here) but simultaneously

-

high enough to not be numerically dominated by the reinvestment of priority fees and MEV, as a fraction of unstaked Ether; \(\alpha^\star\gtrsim r^\star f^\star\).

Inflation will eventually decay though, driving the equilibrium point itself \(s^\star\to1\), though it may take considerable time. This “L2 future” has been recognized by many others: most Ether is staked, with the majority used for settlement of L2 rollups. We’ll discuss it more next time.

Given all the above, we advise caution. Intervening to reduce the issuance yield curve seems quite capable of exacerbating the very problems we seek to avoid.

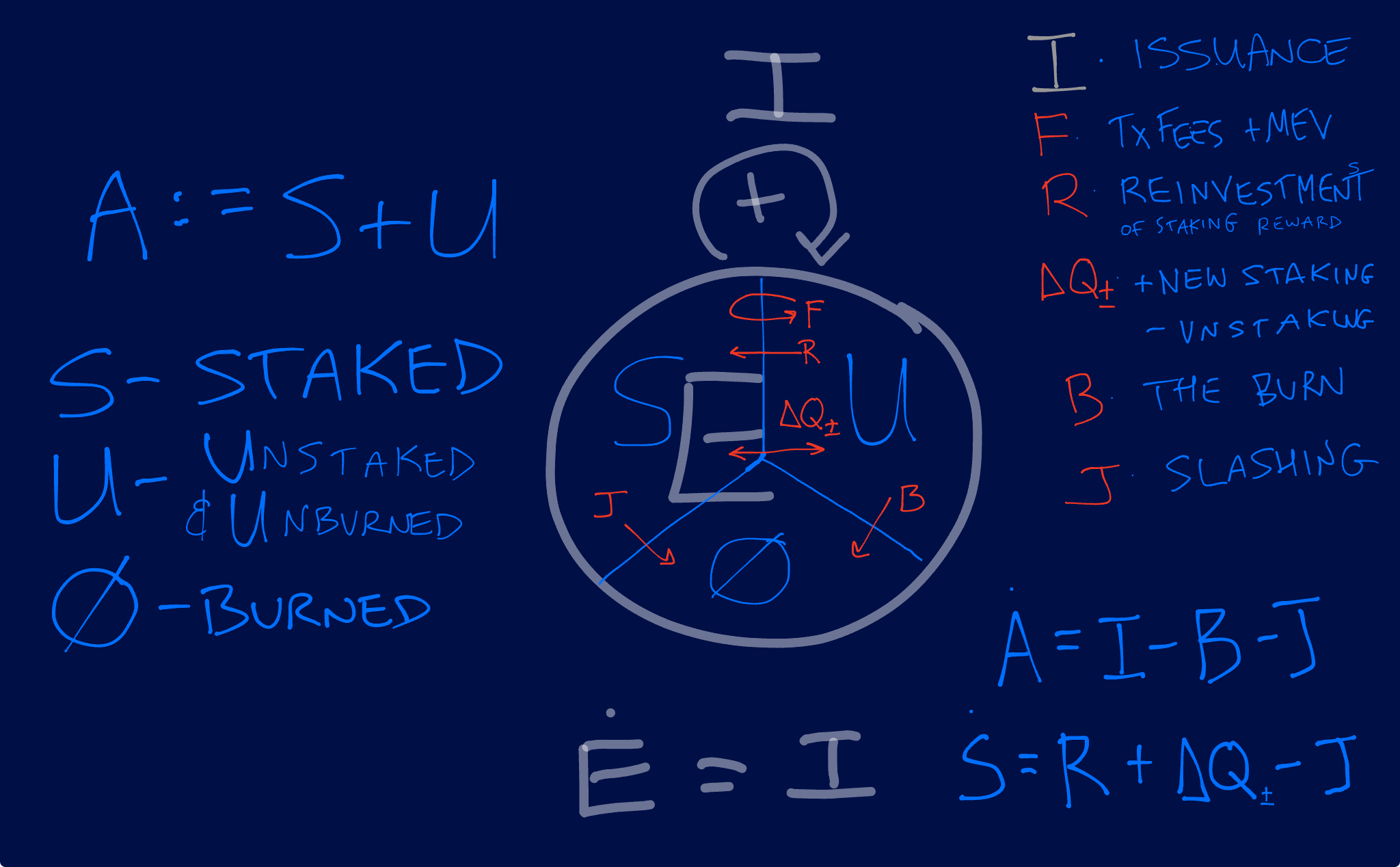

Modeling an Open Zeppelin1

First, a warning! In an act of hubris, and with apologies, but not without reasons2, we have chosen \(S\) to refer to Staked ETH, while others have at times used \(S\) for “circulating (S)upply”, which we call instead \(A\), so \(s=S/A\). Please proceed!

Consider a “balloon” with variable internal compartments. The average size of each is measured by stocks

- (\(S\))taked Ether (participating in consensus) is a compartment, as is

- (\(U\))nstaked unburnt Ether, – containing the (\(V\))alidator reward queue.

- (\(\cancel{O}\)) is all irrecoverable (burned, lost, etc.) Ether, and

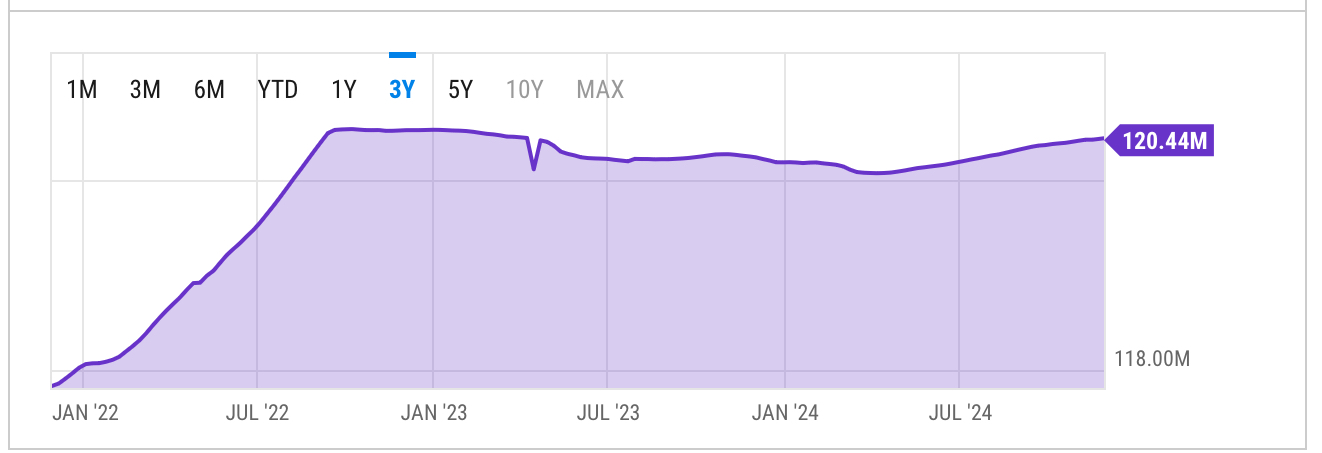

- (\(A\))ccessible/Circul(\(A\))ting Ether supply, \(A=S+U\approx120.4\times10^6\) in Dec 2024.

- \(\mathcal{Q}_\pm\) the Ether in the staking (\(+\)) and unstaking (\(-\)) queues

The net change in time of a stock is written using a dot, such as \(\frac{dA}{dt}:=\dot{A}\)3, the net change in accessible Ether supply. Stocks grow or shrink based on flows which add to or subtract from their derivatives. Here all flows are positive real numbers with units [ETH/yr].

By averaging over “long” timescales (at least quarterly)4 we approximate the staking and unstaking queues as equilibrated, and average over many cycles of the erratic base fee oscillations.

So, our conceptual model:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{rcl} \dot{A} &=& I - B - J\\ \dot{V} &=& I + P - R - K\\ \dot{U} - \dot{V} &=& K + Q_- - Q_+ - F\\ \dot{S} &=& R + Q_+ - Q_- - J\\ \end{array}\]| Flow Name | Symbol | Domain \(\to\) Codomain5 | Constraint |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tx Fees | \(F\) | \(U\to\cancel{O},V\) | \(B+P=F<U\) |

| Base Fees4 | \(B\) | \(U\to\cancel{O}\) | .. |

| Priority Fees | \(P\) | \(U\to V\) | .. |

| Issuance4 | \(I\) | \(\cdot\to V\) | \(I\leq yS\) |

| Slashing | \(J\) | \(S\to\cancel{O}\) | \(J<S\) |

| Unstaking | \(Q_-\) | \(S\to U\) | \(Q_-<S\) |

| New Staking | \(Q_+\) | \(U\to S\) | \(Q_++R<U\) |

| Reinvestment6 | \(R\) | \(V\to S\) | \(R+K+\dot{V}=I+P\) |

| Costs & Profits | \(K\) | \(V\to U\) | .. |

Flows \((B,J,Q_-,\ldots)\) have a “domain” \((U,S,S,\ldots)\), where the flow is coming from, and a “codomain” \((\cancel{O},\cancel{O},U,\ldots)\), where the flow is going to.5 Flows obey constraints, often expressed as (in)equalities relating a flow to its domain. In case you’ve forgot or are skimming, (co)domains are summarized in this glossary.

In response to the concerns about \(s\to1\), the recent Deneb upgrade implemented EIP 7514, an upper limit on \(R+Q_+\) chosen so as to not limit any present flows. We also ignore the pre-existing symmetric limits on (un)staking \(Q_\pm\). The purpose of our models is to show, in the absence of such limits, where the dynamics push the system. If you wish to study an extreme of dynamics post-Deneb, you could make \(R+Q_+\) constant; we will revisit EIP 7514 in our next post in this series, on staking composition. So the constraints (\(Q_-<S,Q_+<U\)) could be tightened significantly, but more accurate upper limits would play little role in our analysis.

A few flows deserve specific comment: \(I\) and \((R,Q_+,K)\).

Bounding Issuance

All of these stocks and flows, \((I,S,\ldots)\), are moving time-averages over spot values \((I^\bullet,S^\bullet,\ldots)\) defined at a given block. For issuance, we’ll assume that

-

Issuance is sublinear \(1\ll I\approx yS\ll S\)7 to avoid discouragement attacks, and that

-

The large-stake scaling of yield (like, on a log-log plot) is not substantially altered by time averaging \(\frac{\partial{d\log{y}}}{\partial{d\log{S}}} \approx\frac{\partial{d\log{y}^\bullet}}{\partial{d\log{S^\bullet}}}\).8

The first is common and almost certainly an overestimate with $I\leq{yS}$ more precise. We reason as follows. We can express spot issuance as a known function of the yield curve \(I^\bullet = y^\bullet S^\bullet\). From this we obtain an inequality for the quarterly-averaged issuance $I\leq yS$ using time-covariance.

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{rcl} I &=& \frac{1}{\tau}\int_{t-\tau}^ty^\bullet S^\bullet dt'\\ &\approx& yS + \frac{1}{\tau}\int_{t-\tau}^t(y^\bullet-y)(S^\bullet-S)dt'\\ &=& yS - |COV(y^\bullet,S^\bullet)|\\ I &\leq& yS \end{array}\]Other approximations are also possible, see guide. This should work for any positive definite yield curve with finite slope, erring in a conservative direction without explicit dependence on the present curve $y^\bullet = y_0(1)/\sqrt(S^\bullet)$ with $y_0(1)\approx166.3$/yr. We deem this a good direction in which to err in light of our results concerning (the lack of) runaway inflation.

Bounding Reinvestment

Reinvestment of staking rewards by validators \(R\) is achieved by staking a new validator from existing rewards, or post-Electra increasing the stake on an existing validator. While clearly a stochastic process, we approximate the net effect as smooth on timescales of at least \(\tau\). \(R\) represents a feedback loop \(S\overset{+}{\rightsquigarrow}S\) quite evidently related to the potential positive-feedback between staking and inflation that people have found concerning.

To express this concept succinctly in one flow variable, we require that the averaging timescale \(\tau\) be adjusted upward until most validators claim and reinvest the bulk of their staking rewards within it. That is \(\dot{V}=0\), so \(R+K=I+P\) so \(R\leq I+P\). The quantity \(r=R/(I+P)\), the ratio of staking rewards reinvestment over issuance and priority fees is one of the distinguishing features of our model, and also why we have split the staking queue flow \(R+Q_+\). These are our motivations:

- Modeling \(r\) is absolutely necessary to model LSTs.9

- We want to separate the transient externally-driven dynamics \(Q_+\) from the long-term endogenous feedback \(R\),10

- \(r\) could be measured and monitored with onchain data, and

- Low $r$ might be hazardous.

If the \(\tau\) required to achieve \(r=R/(I+P)<1\) in practice becomes too large, one might refine the approximations used to model issuance, or use data to better model \(\dot{V}\). In neither case do we expect this to make a huge qualitative difference for the issues considered here, but please, prove us wrong!

Intensive Flows give Dynamical Systems

Flows obey inequalities, usually as a fraction of the source, except for $r,b$. We convert these inequalities; for each uppercase extensive flow \((J,F,B,\ldots)\) we define a lowercase intensive variable11 \((\jmath,f,b,\ldots)\) with [units]: the fractions [1] and fractional rates [1/yr]. In forming these, the ideal is to apply the tightest available bounds that still capture the asymptotic behavior7 in the limit of interest \(S\to A\). We do not assume the intensive parameters are constant, but suppress their dependence for readability. Unless otherwise stated, the intensives are functions of the dynamical variables and time, so the burn: \(b(A,S,t)=B/F\).12

Table of Flows

| Flow Name | Symbol | Domain \(\to\) Codomain5 | Constraint | Intensive | Range [Units] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tx Fees | \(F\) | \(U\to\cancel{O},V\) | \(0<B+P=F<U\) | \(f:=F/U\) | \(f\in(0,1)\) [1/yr] |

| Base Fees4 | \(B\) | \(U\to\cancel{O}\) | .. | \(b:=B/F\) | \(b\in(0,1)\) [1] |

| Priority Fees | \(P\) | \(U\to V\) | .. | \(1-b=P/F\) | \(1-b\in(0,1)\) [1] |

| Issuance4 | \(I\) | \(\cdot \to V\) | \(0<I\leq yS\) | \(y\approx I/S\) | \(0<y(S)\ll 1\) [1/yr] |

| Slashing | \(J\) | \(S\to\cancel{O}\) | \(0<J<S\) | \(\jmath:=J/S\) | \(\jmath\in(0,1)\) [1/yr] |

| Unstaking | \(Q_-\) | \(S\to U\) | \(0<Q_-<S\) | \(q_-:=Q_-0/S\) | \(q_-\in(0,1)\) [1/yr] |

| New Staking | \(Q_+\) | \(U\to S\) | \(0<Q_++R<U\) | \(q_+:=Q_+/U\) | \(q_+\in(0,1)\) [1/yr] |

| Reinvestment6 | \(R\) | \(V\to S\) | \(R+K=I+P\) | \(r:=R/(I+P)\) | \(r\in(0,1)\) [1] |

| Costs & Profits | \(K\) | \(V\to U\) | .. | \(1-r=K/(I+P)\) | \(1-r\in(0,1)\) [1] |

The use of intensive variable parameters and the approximation \(\dot{V}\approx0\) allows us to reshape our conceptual model into one that is defined in its own dynamical and intensive variables, a dynamical system. We’ll build this up one step at a time. As you follow along you may find it useful to look at models in python. You can use these extremely rough estimates of constant parameters along with $A_{now}\approx120e6,\ s_{now}\approx.3$ as a start for the models that follow.

from ethode import *

@dataclass

class ConstParams(Params):

y1: 1/Yr = 166.3

b: One = 5e-1

f: 1/Yr = 8e-3

j: 1/Yr = 1e-5

r: One = .65

qs: 1/Yr = 1e-4

qu: 1/Yr = 1e-4

s1: ETH = 1

def yld(self, S:ETH, **kwargs) -> 1/Yr:

return self.y1 * np.sqrt(self.s1 / S)

\((S,U)\); not just a UNIX Command!

With the above, you should be able to construct the following \((S,U)\) system:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{rrrlcrl} \dot{S} &=& \ \ (ry-\jmath-q_-) & S & + & \ \ \left(q_++r(1-b)f\right) & U\\ \dot{U} &=& \left((1-r)y+q_-\right) & S & - & \left(rf+(1-r)bf+q_+\right) & U\\ \end{array}\]These coefficients of staked \(S\) and unstaked \(,U\) ETH are miserably complicated-looking, but as written they are all (but one) positive, and so we can reason about this model’s evolution. Specifically, so long as \(ry(S)>\jmath+q_-\) staked ETH \(S\) just continues growing and growing. In contrast it is harder for \(U\) to get as big, limited by its own loss term \(-\left(rf+(1-r)bf+q_+\right) U\). At some point in the (far) future \(S\) becomes big enough that \(ry(S)<\jmath+q_-\) and the system becomes capable of oscillation, depending on parameters and a zoo of partial derivatives.13

@dataclass

class SUConstParams(ConstParams):

init_conds: ETH_Data = (('S', 120e6 * .3), ('U', 120e6 * .7))

tspan: tuple[Yr, Yr] = (0, 100)

@dataclass

class SUConstSim(ODESim):

params: Params = field(default_factory = SUConstParams)

@staticmethod

def func(t:Yr, v:tuple[ETH, ETH], p:Params) -> tuple[ETH/Yr, ETH/Yr]:

S, U = v

dS = (p.r * (y := p.yld(S)) - p.j - p.qu) * S + \

((rf := p.r * p.f) * (1 - p.b) + p.qs) * U

dU = ((1 - p.r) * y + p.qu) * S - \

(rf + (1 - p.r) * p.b * p.f + p.qs) * U

return dS, dU

su = SUConstSim()

su.sim()

These dynamic variables are kind of boring, but critically and unlike \((A,S)\), there are no extra conditions (such as \(S<A\)) that we haven’t told the math about. The equations are not stiff; they can be simulated without too much pain, though we always recommend to backup a simulation result with some analysis: numerical regimes can miss important dynamics when perturbation series are insufficient. Most importantly, the variables of interest in the ongoing debate are functions of \(S,U\), so we lose nothing by calculating them post-simulation; we’ll demonstrate how. Even as we change dynamical variables for intuition building, we recommend using models like \((S,U)\) as a base for simulation whenever possible.

Inflation

Inflation is used to refer to many things, but here we mean specifically the quarterly fractional change in accessible Ether. Consider \(\alpha:=\dot{A}/A\approx(I-B-J)/A\) in light of the above table. In general and under the existing yield curve we have (where \(\beta=bf=B/U\)):14

\[\displaystyle \alpha\ \approx\ y(sA)s-\beta(1-s)-\jmath s \ =\ y_0(1)\sqrt{s/A}-\beta(1-s)-\jmath s\]You can explore this by adding alpha(), sfrac() as @output methods

@dataclass

class SUaConstParams(SUConstParams):

@output

def sfrac(self, S:ETH, U:ETH) -> One:

return S / (S + U)

@output

def alpha(self, S:ETH, U:ETH) -> 1/Yr:

s = self.sfrac(S,U)

return self.yld(S) * s - self.b * self.f * (1 - s) - self.j * s

@dataclass

class SUaConstSim(SUConstSim):

params: Params = field(default_factory = SUaConstParams)

su_a = SUaConstSim()

su_a.sim()

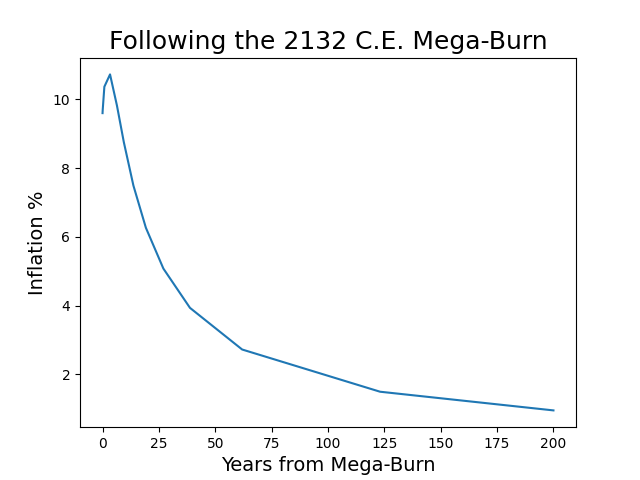

Persistent inflation cannot maintain

A key feature of \(\dot{A}\) under the current yield curve \(y_0(S)\) is sublinear issuance \(I\leq yS\lesssim S\), chosen to avoid discouragement attacks. Because of this, positive inflation cannot maintain indefinitely. We will demonstrate with the existing yield curve, but the argument is general. Unusually for this blog post, we show most of the steps so the argument is hopefully understood. Elsewhere we use $I\approx yS$, but here we use $I\leq yS$ as greater rigor is appropriate.

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{rcl} dA = \alpha Adt &\leq& \left(ys-\beta(1-s)-\jmath s\right)Adt\\ dA &\leq& ysAdt = y_0(1)\sqrt{sA}dt \leq y_0(1)\sqrt{A}dt\\ \int_{A(0)}^{A(t)}A^{-1/2}dA &\leq& \int_0^{\ t} y_0(1)dt\\ \left.\frac{1}{2}\sqrt{A}\right\|^{\sqrt{A(t)}}_{\sqrt{A(0)}} &\leq& y_0(1)t\\ A(t) &\leq& \left(\sqrt{A(0)}+2y_0(1)t\right)^2\\ \therefore A(t) &\lesssim& t^2 \ll e^{kt} ~\forall ~\mathrm{const.}~k>0 \end{array}\]The last line is Vinogradov asymptotic notation, used in the rest of this post7 For two positive functions, \(g\) dominates \(f\), written \(f(t)\ll g(t)\) just when \(\lim_{t\to\infty}[f(t)/g(t)]=0\). When the limit is a non-zero constant we say $f\sim g$. We use $\gg/\ll/\sim$ for numbers as well, by which we mean the order of magnitude is much larger / much smaller / similar.

The point. Since supply \(A(t)\) is eventually less than a powerlaw of \(t\), it is subexponential. Thus, no positive rate of Ether supply expansion can maintain indefinitely.15

This does not mean we would find every intermediate inflation rate pleasant. Following surges in \(Q_+\) and/or drops in supply, inflation can accelerate quite alarmingly. A good example will be the Ethereum staking-mania following the 2132 Atlantia-v-Eurasia market crash, in which 99% of present-day Ether will have been burned.

@dataclass

class MegaBurnParams(SUaConstParams):

init_conds: ETH_Data = (('S', 1.2e6 * .4), ('U', 1.2e6 * .6))

tspan: tuple[Yr, Yr] = (0, 200)

b: One = 1e-3

qs: 1/Yr = 2e-1

@dataclass

class MegaBurnSim(SUaConstSim):

params: Params = field(default_factory = MegaBurnParams)

zomg = MegaBurnSim()

zomg.sim()

We aren’t excited to hodl through multiple decades of 10% inflation, and we expect you aren’t either! Silliness aside, we encourage you to find more realistic scenarios in which such sustained inflation occurs.

We mean to separate concerns, not dismiss inflation as a problem. Unpleasantly high inflation in the medium term, even if that “medium term” lasts decades, is a dynamics problem, not an equilibrium problem, and so dynamical solutions (like EIP 7514) seem better suited. Unfortunately we will see that given the above, \(s^\star\to1\) is an equilibrium problem.

Staking Fraction

We have equations for \(\dot{A},\dot{S}\), what about \(\dot{s}=d(S/A)/dt\)? Using the quotient rule \(\dot{s}=\frac{\dot{S}}{A}-s\frac{\dot{A}}{A}\), and after an algebraic massage, we obtain for staking fraction

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{rcl} \dot{s} &=& y(sA)\ (r-s) + \\ && \left[q_++f(1-s)\left(bs +(1-b)r\right)\right]\cdot(1-s) + \\ && \left[\jmath(1-s+r)+q_-\right]\ (0-s). \end{array}\]The coefficients of \((r-s),\ (1-s),\ (0-s)\) are variable but positive. Recalling how \(s\) increases just when \(\dot{s}>0\), these terms draw \(s\) toward respective points \(r,1,0\). We emphasize that the action of yield \(y\) is \(x\to r\), which may not be the same as \(x\to1\).

As expressed by the quotient rule, an increase in staking fraction can be driven by more people staking, and/or it can be driven by a reduction of the inflation rate. The latter can be achieved in principle by a reduction of issuance relative to the base fee “burn rate”. Because of this quotient rule tradeoff, issuance plays a beneficial “infrastructure” role in moderating staking fraction, drawing it toward \(r\), which can be less than one.

\((A,\alpha,s)\) Dynamical System

There are many reasons, especially in the context of the world economy, to care about total circulating supply \(A\). Recent discussions however have focused most on inflation \(\alpha=\dot{A}/A\), the growth in supply over time. It also turns out that modeling inflation \(\alpha\) directly simplifies our analysis of the \((A,s)\) system considerably.

Let subscripts denote partial derivatives \(x_y:=\frac{\partial{x}}{\partial{y}}\). Using the correct partial derivative relations for variables \((A,\alpha,s,t)\)3 we have

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{rcl} \dot{A} &=& \alpha A\\ \dot{s} &=& \alpha(r-s) + (rf+q_+)(1-s) - (q_-+(1-r)\jmath)s\\ \dot{\alpha} &=& \xi\dot{s} - \gamma\alpha s +\chi \end{array}\]Where the new greek letters are fractional rates, defined below, and \(y':=\frac{dy}{dS}\).

-

\(\mu:=\beta_\alpha(1-s)+\jmath_\alpha s\) is the implicit sensitivity of the inflation loss-term to increases in inflation. We judge \(0\leq\mu\); if anything inflation increases burn and slashing fractional rates.16

-

\(\xi:=(y+y'A+\beta-\beta_s(1-s)-\jmath-\jmath_s)/(1+\mu)\) is the net correlation between changes in \(s\) and changes in \(\alpha\) normalized by \(1+\mu\). \(\xi\) can be of either sign. Under the current yield curve \(y_0+\frac{dy}{dS}A=y_0(sA)(1-1/(2s))\), which changes its sign at 50% ETH staked.

-

\(\gamma:=\jmath_{\log{A}}s+\beta_{\log{A}}(1-s)+s\|y'\|A\) is a positive coefficient expressing how quickly \(\alpha\to\alpha^\star\), and the partials are constant when initial supply is known.17 We have extracted the sign from the final term because sublinear issuance implies \(y'<0\); under the current yield curve the term \(sA\|y'\|=\frac{1}{2}y_0(sA)\).

-

\(\chi:=-\jmath_ts-\beta_t(1-s)\) represents externalities affecting the inflation loss term encoded as explicit time-dependencies. We neglect externalities \(\chi\approx0\) because we have nothing intelligent to say about them, but you might not want to.

We don’t recommend modeling this numerically; these equations are stiff. We use it for mathematical analysis only.

Separation of Timescales and \(\alpha>0\)

Observe that every term in \((\xi,\gamma)\) are small fractions, fractional rates, or derivatives thereof. Indeed, when \(\alpha\approx0\) and sensitivities are weak, \(\|\xi\|\sim\gamma\sim y\) obtains. Generally if \(\|\xi\|,\gamma\ll1\) then the derivatives obey \(\|\dot{\alpha}\|\ll\|\dot{s}\|\): a separation of timescales. For durations when this obtains, one or more periods at intermediate times, inflation can be usefully approximated as a parameter instead of its own dynamic variable, with staking fraction equilibrating to \(s^\star\) more quickly than \(\alpha^\star\) equilibrates.

Does this hold presently? For a sanity-check, a quick look at YCharts since Sept 2022 (the Merge) shows that \(s,\dot{s}\) do indeed seem to vary over a much greater range than \((\log{A},\alpha)\) under Proof-of-Stake.

For the remainder of this post, we will assume this obtains. Anecdotally, even when it does not, the revealed interplay between inflation and staking fraction shows up, and is a very important concept for Ethereum macroeconomics.

Staking Fraction in 1D

Recall our approximate equation for the fraction of staked ETH \(s\), in which all coefficients are positive but inflation \(\alpha\):

\[\displaystyle \dot{s} = \alpha\ (r-s) + (rf+q_+)\ (1-s) + (q_-+(1-r)\jmath)\ (0-s)\]So assuming \(\|\dot{\alpha}\|\ll\|\dot{s}\|\), let us examine the fixed point \(s^\star\) during a period in which we may treat inflation as constant \(\alpha=\alpha_{const}\).

\[\displaystyle s^\star = \frac{r^\star(\alpha_{const} + f^\star) + q_+^\star }{ m^\star := (\alpha_{const} + r^\star f^\star + q_+^\star + q_-^\star + (1-r)\jmath^\star) } = 1 - \frac{(1-r)\jmath+q_-}{m^\star} - \frac{\alpha_0(1-r^\star)}{m^\star}\]We will see that without \(\alpha>0\) an interior market equilibrium is very unlikely. First, as a thought experiment, consider \(\alpha=0\).

Concerning Churn

A fixed point \(s^\star(\alpha=0)<1\) would require either high churn or a persistent unstaking/capitulation of existing validators \(q_-+\jmath>0\). Validators try to minimize slashing as intended, but what would a large unstaking flow \(q_-s\gtrsim rf\) at \(s^\star\) mean?

High unstaking requires churn, a persistent supply of new validators to take their place \(q_+^\star(1-s)\sim q_-s\gtrsim rf\), or it is only a transient and \(q_-^\star\ll rf\); recall that reinvestment by existing validators is not counted in \(q_+\). Persistently high unstaking \(q_-\sim rf\) could only describe a market equilibrium if one group of stakers was actively capitulating and withdrawing their stake, while another group with a higher \(r\) were aggressively reinvesting in their business, and their reinvestment of fees and MEV offset the unstaking, adjusted for inflation.

High churn, not counting reinvestment, cannot maintain forever: eventually there will be no new Capitulators left, and \(s^\star\) must once again grow as required by the Reinvestors’ higher \(r\), so \(s^\star\) was not a fixed point at all. So \(q_-^\star\ll (rf)^\star\).

Similarly, at some point everyone who wants to stake should have staked. If we judge the \(\tau\)-averaged flows due to the issuance of new humans and the burn rate of legacy humans to be small, additional validators count overwhelmingly toward \(r^\star\) and \(q_+^\star\ll(rf)^\star\). Thus, the fixed point \(s^\star\) simplifies to

\[\displaystyle s^\star \approx r^\star \frac{\alpha_{const} + f^\star}{ \alpha_{const} + r^\star f^\star + (1-r^\star)\jmath^\star}\]We will explore the stability of this fixed point below, and based on the range of \(\alpha\) categorize three basic behaviors.

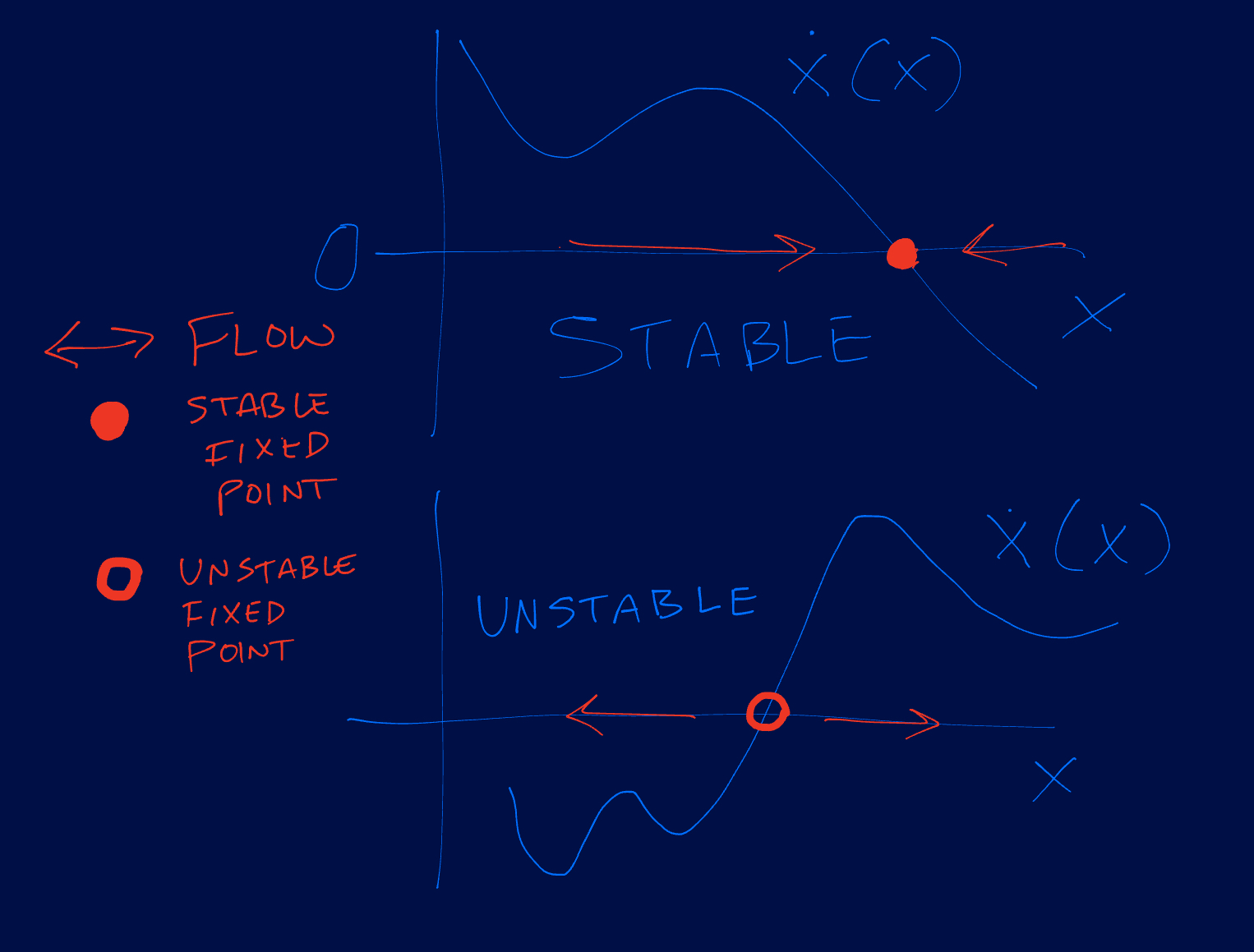

Stability in One Dimension

Fixed-points are market equilibria just when they are stable.18 Local stability is easy to asses for one dimensional maps. In general a fixed point is locally stable when small changes (perturbations) shrink over time. For a continuous map \(\dot{x}(x)\) like ours, this concerns the derivative of the RHS at the fixed point. If it is negative, then small perturbations shrink and the fixed point is a stable sink, and $x$ “flows”19 toward it. If the derivative is zero, the fixed point is a degenerate center, unrealistic outside of physics. If positive, the fixed point is an unstable source and repels $x$.

Specifically for staking fraction, we want the sign of \(\left.\frac{\partial\dot{s}}{\partial s}\right\|^\star\) to determine whether \(s^\star\) is (un)stable. We will be ignoring the partial derivatives (“sensitivities”) by assuming they are small in comparison with their corresponding intensives.20 The full no-churn stability condition, including variations in $\alpha$ is (with subscripts denoting partials)

\[\displaystyle (\alpha^\star/f^\star)\ +\ r\ +\ (\jmath^\star/f^\star)\ \ >\ \ \log{r}_{\log s}^\star\left[ (\alpha^\star/f^\star)\ +\ (1/r^\star-1/s^\star) (\alpha/f)_r^\star\right]\]If we assume that sensitivities are dominated by their respective intensives, this reduces to a simple \(\alpha^\star+r^\star f^\star \gtrsim -\jmath^\star\).

Weak Deflation. If \(-(rf+(1-r)\jmath)^\star<\alpha_{const}\leq0\) then an interior market equilibrium \(s^\star\) requires high slashing, as we argued before based on Churn. All other things being equal, it is also less stable. Assuming low slashing continues, as validators must pay the cost themselves so are incentivized to minimize it, then $s^\star>1$ and runaway staking is inevitable if the fixed point is stable: the numerator is larger than the denominator. If unstable, $s$ is pushed toward zero, and in practice becomes unpredictable by our model: externalities intervene to do… something.

Strong deflation. Consider now \(\alpha<-(rf+(1-r)\jmath)^\star\). This could happen for instance if the issuance curve were reduced particularly bluntly, or changes in fundamentals drove either MEV or the base fee (and thus \(f\)) to a persistently higher amount, such that \(ys\ll bf(1-s)+\jmath s\). These conditions cannot maintain of course. You don’t need differential equations to see that \(\alpha<0\) shrinks \(A\), which eventually raises \(y(sA)\). But as a temporary intervention to tame runaway staking fraction how would this work? Our fixed point is negative and the simplistic “ignore the constants” stability criteria is no longer met. So again, 100% staking becomes inevitable (the source $s^\star<0$ pushes $s$ instead of pulling it), or (more likely) the behavior simply becomes unpredictable as externalities intervene.

There’s a lot of potential complexity here, but none of it is desirable! If you don’t like inflation, wait until you try deflation! In all seriousness, while we agree largely with the aversion to inflation in the context of national economies, it is really important to recognize that those economies have a level of demand diversity and robustness that Ethereum at present can only dream of. One day hopefully we will have the luxury of bemoaning inflation’s effects on hodlers, and reducing it, without fear of the infrastructural dynamics of these market equilibria running amok.

Medium $r$; Low Inflation; Even Lower Fees

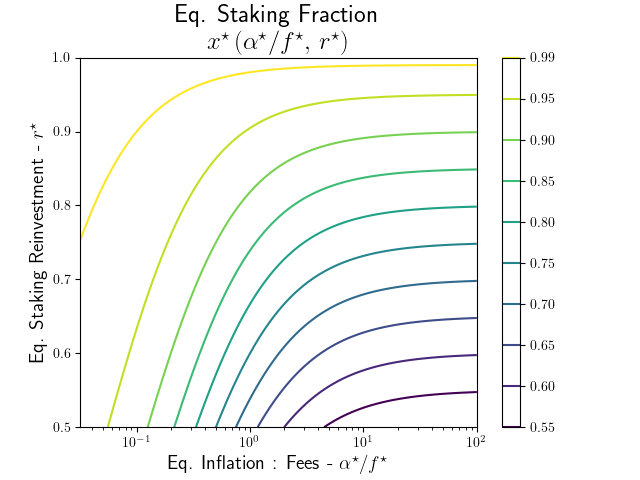

Well, that was deflating! Let’s cheer ourselves up by considering the behaviors under \(\alpha_{const}>0\). A positive role for inflation can be seen in the contours of the market equilibrium staking fraction \(s^\star\) corresponding to \(\dot{s}=0\), shown here with \(\alpha^\star=\alpha_{const}\) and no slashing.

.

.

To find the equilibrium values \((\alpha^\star/f^\star,\,r^\star)\) necessary to achieve a desired staking fraction \(s^\star\), simply pick a colored contour in the figure: these are the values of constant \(s^\star\). For every point on this curve, the equilibrium inflation:fee ratio \(\alpha^\star/f^\star\) is the x-coordinate, and the equilibrium reinvestment ratio \(r^\star\) is the y-value.

A breakdown of limiting behaviors is illustrative under positive inflation. For any value of non-negative inflation, \(r^\star\) is a lower bound for the equilibrium staking fraction we should expect. If inflation dominates fees, \(\alpha_{const}\gg f^\star\) then \(s^\star\) is larger by a very small amount than \(r^\star\), while if fees dominate inflation \(0<\alpha_{const}\ll f^\star\) then \(s^\star\) becomes insensitive to non-zero reinvestment ratio and \(s^\star\to1\). In the intermediate range $r^\star f^\star\sim\alpha^\star$, $r^\star < s^\star$ still but the gap is bigger.

For a numerical comparison, eyeballing charts (so extremely rough approximations here, possibly off by an order of magnitude, maybe more) \(rf \approx .004\sim.005\approx\alpha\) so to within 15-20% error above, \(s^\star\approx r^\star\) over the range of \(r\in(.5,.75)\) inferred from the Lido yield rate. Clearly we are not yet at equilibrium, or $r$ is much lower than our extremely rough estimates.

How the transient values \((\alpha_{now}/f,r)\) relate to the true equilibrium values \((\alpha^\star/f^\star,r^\star)\) depends on some considerations:

-

If indeed churn dies down and slashing stays relatively rare, then \(r\) increases to reflect the growing share of businesses that reinvest the most; \(r^\star\approx r_{max}\), where \(r_{max}\) is assessed over all staking pools with at least 10% of \(S\).

-

We are holding \(\alpha_{const}=\alpha^\star\), so \(\alpha_{now}\approx\alpha^\star\) but a more sophisticated approximation is likely possible keeping within the two-timescale context… maybe you’ll find one!

Runaway \(r\) from Inflation pressure

Could the sensitivity \(r_\alpha\) be sufficient such that even at intermediate timescales we see \(s^\star\to1\)? This is certainly possible; per the arguments of Ethereum researchers, high inflation could still lead to runaway staking if \(r\) is sensitive enough.

In our model the net effect of inflation on staking fraction equilibrium is reflected by taking the derivative \(0<\left.\frac{ds^\star}{d\alpha}\right\|^\star\) assuming \(r,f\) are implicit functions of \(\alpha\). That is, the necessary condition for inflation to push the market equilibrium \(s^\star\) itself into runaway staking is (see below for explanation):

\[\displaystyle 1 \ \ < \ \ \left(\frac{\partial\log\ r}{\partial\log\ \alpha}\right)^\star \cdot \frac{1 + \alpha^\star/f^\star}{1 - r^\star} \ \ + \ \ \left(\frac{\partial\log\ f}{\partial\log\ \alpha}\right)^\star\]In practice it all depends on what ETH users consider sufficiently “high” inflation to respond; the above conditions just reflect a quantification of this preference. We hope that this work can be built upon to determine what threshold of inflation or business conditions satisfy the above condition. No mean feat, but it would help focus inflationary pressure arguments into empirically measurable assertions that can be tracked for Ethereum health.

Whence “Mr”; Dangers of Low $r$

Before you start advocating for “EIP 7514 On Steroids” on crypto twitter (that is, throttling the staking queue to prevent $r$ from rising, such as due to inflation-pressure), consider the danger of low staking, that is low $r$ in the absence of significant churn. In the simplified staking fraction equation, the term $\alpha(r-s)$ is positive only when $s<r$ and $\alpha>0$… what if $r\to\epsilon\ll{s_{now}}$ for some reason? Then the only positive term $(rf+q_+)(1-s)$ gets very small in the absence of new staking. But, given sufficient inflation and fees and very marginal sensitivities, the stability requirement $\alpha+rf+\jmath>0$ could still obtain, so the new fixed point, presuming inflation maintains in LI;ELF territory, $s^\star\sim\epsilon$ remains stable.

That’s quite a lot of ifs, but consider exponential growth of supply under present issuance: $y_1\sqrt{sA}$… $A\sim e^{\alpha t}$ can maintain so long as $s\sim\epsilon + s_{now}e^{-\alpha t}$. For roughly $\alpha^{-1}\log\epsilon^{-1}$ Ethereum could in principle experience simultaneously lowered security, and consistent inflation. For small $\epsilon$ and $\alpha\sim.1$ that’s more than a decade in principle. Whether this has any bearing on reality, we don’t know, but its worth being aware of. In the guide we will be adding upper limits on the time-duration of inflation as time-permits.

Concluding Discussion

We saw above a few things:

- Reinvestment \(r\) is a lower-bound for the staking fraction fixed point \(s^\star\) unless Ether is deflating, when likely $s\to1$ or the dynamics are unstable.

- Low (but positive) inflation moderates staking fraction closer to this lower bound at intermediate timescales

- Positive inflation cannot maintain indefinitely, so eventually \(s^\star\to1\).

Conceptually, how can inflation moderate staking fraction, though? Shouldn’t more staking lead to more issuance, which leads to more inflation, etc.? Briefly the reasons are:

- Short \(Q_+\) vs. Long Term \(R\) Investment

- The Quotient Rule \(\dot{S}=\dot{S}/A-s\dot{A}/A\)

Short Term vs. Long Term.

Novel investment in staking \(Q_+\) is driven largely by speculation, and new users encountering Ethereum. \(Q_+\) acts to increase staking fraction, as seen above, and indeed the glut in \(Q_+\) since the Merge may have been the source for much of the alarm that prompted this study. Novel speculative investment must eventually dry up, and be replaced by long-term investment \(R\), because

- everyone with money who wants to stake eventually will, so will be counted in \(R\) not \(Q_+\)

- any business that wants to stay in business cannot consistently reinvest more than its revenue \(R\leq I+P\) (issuance plus priority fees).

Of the long term signal \(R\), only the issuance portion of reinvestment, that is the part that contributes to inflation, can moderate \(s\), which brings us to the quotient rule.

The Quotient Rule

\[\displaystyle \dot{s}\ \ =\ \ \frac{\dot{S}}{A}\ -\ \frac{S\dot{A}}{A^2}\ \ =\ \ \frac{\dot{S}}{A}\ -\ s\alpha\]What increases \(s\) is any increase in staked Ether \(S\), but also any net decrease in \(A=S+U\). Inflation \(\alpha\) increases both \(U\) and \(S\), because some of that increase is used to meet costs and take profit \((1-r)\alpha\), which increases \(U\) relative to \(S\). In contrast, the reinvestment of transaction fees can only ever increase \(S\) at the expense of \(U\). Thus transaction fees always act to increase staked fraction, while the effect of inflation depends on the relative values of reinvestment ratio and staking fraction.

So, while we could certainly model reinvestment differently, and there are lags we are blithely integrating over, we think that these market forces will still act as described above in a different model. It is possible that even during sustained inflation, these effects will be unable to prevent the upward creep in \(s\), because \(r\) is too large, or the sensitivity of \(r\) to inflation at equilibrium is too great, a condition which we mathematized above. In fact we expect that every argument about inflation effects driving increased staking, overpaying for security, etc. could (perhaps should) be rephrased in terms of reinvestment of staking rewards. All these critically depend on the preferences of ETH users for, and thus their behavior in reaction to, inflation rate etc., which thusfar are not measured, as far as we know. We encourage the community to rectify this!

Can reflexivity prevent \(s\to1\)?

Regarding the possible effects of reflexivity. We have neglected even discussing oscillations in \((S,U)\), even though the model is plainly capable of such behavior under different parameters or when coupled to price. Why such negligence? If cycles do arise, we expect market participants, anticipating such cycles, would act to profit off of these cycles in a way that should reduce them. Buy late in the inflation cycle, sell late in the deflation cycle, etc. This would show up in our model via the partial derivatives including externalities.

Notably though, we only expect this to happen because it does not require the coordination of market participants: each individual blindly pursuing their own utility should help en masse control these oscillations, or they were never very great to begin with.

Could there be a similar effect with staking fraction or inflation? In short we have no idea, but put it as a challenge to the reader. Can you devise a cryptoeconomic protocol or trading strategy that forestalls the seemingly inevitable \(s^\star\to1\)? If not, can you prove this is impossible?

Should We Change \(y\)?

So, finally… should the Ethereum community reduce issuance?

Glib answer

No.

Short answer

Let’s adopt a dynamical solution to a dynamical problem. If you are very inflation averse or you want to slow down the transition to high staking, please study and simulate downward adjusting the constants in EIP 7514, adopted during the Deneb upgrade. This already directly limits \(R+Q_+\), but was very nicely designed to not interfere with existing staking flows. It would be particularly interesting to see if $R$ can be safely decoupled from limits on $Q_+$, to avoid the potential danger of low-$r$ scenarios. EIP 7514 does not solve, and does not claim to solve, the long term problems, but we have been forced to conclude that reducing issuance doesn’t solve them either!

Long answer

Ask the users, especially the validators, especially the LSPs. Model user preferences so that the demand curve becomes semi-empirical instead of theorized. Near-100% staking seems to be baked-in eventually, as persistent inflation cannot sustain under an issuance yield curve designed to avoid discouragement.

So the question becomes essentially “How bad will it get in the meantime?” We recommend of course that you use these tools to run simulations. But that is only half the answer… this is really a question about user preferences. Austrian School devotees may be so inflation-averse that they are already staking all their previously-liquid ETH at \(\alpha\approx0.5\)%/yr. In contrast users who were content to grow up with fiat currencies during periods of \(\approx3\)% inflation or even worse might not care, or would just stake in Compound or buy stETH.

For users seeking to passively preserve wealth, staking in Compound (or Aave, or whatever) is ideal for generating raw Ether demand, of course. Staking in LSTs, such as stETH, though concerning from a governance angle, may present less of an issue than some have feared. LSPs must share some yield with users in order to have users, but if they want to stay in business they must maintain \(r_{LST}<1\), and both profit-taking and covering fiat-denominated costs go into unstaked Ether $U$.

So how high can \(r_{LST}\) go before LSPs find the loss of gross profits unacceptable? Great question. We will see next time that as many have recognized, the entity/group $i$ that can maintain the highest \(r_i\) wins the race eventually. It’s worth noting however that if you apply price uncertainty via a risk-discounting rate of, well anything really, you will see that the “maximize \(r_{mine}\)” strategy is far from the most profitable, risk-adjusted. Of course, a speculative investor seeking to profit from our analysis would find our study woefully short of details. Put another way, since you have insisted on reading the “long answer”, we will end with the classic and cowardly refrain of academics and academic-adjacents everywhere “it requires more research!”

Dynamical Systems References

We hope to develop the ethode guide so it can serve a pedagogical role. For now we have assumed some basic familiarity with nonlinear dynamics, asymptotic methods, etc. at the level of the first few of Prof. Steven Strogatz youtube lectures.

Highly Recommended books in order of increasing difficulty and sophistication if you decide you want to understand this stuff:

-

Kun (2020) A Programmer’s Introduction to Mathematics

-

Strogatz (2024) Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos

-

Hirsch, Smale and Devaney (2003) Differential Equations …

-

Bender and Orszag (1997) Advanced Mathematical Methods for Scientists and Engineers

-

Arnol’d (Ed.) the Dynamical Systems Series - esp. V (1994) Bifurcation and Catastrophe

Glossary of Things That Have Dots or Dot-Adjacent Shapes

Unfortunately the fonts used in markdown on the blog are not the greatest at rendering nicely for some of the chosen syntax, especially on certain monitors/browsers. Due to feedback from people with bleeding eyes, we can at least offer this table. We also included, or tried to include, the common variables not present in other tables.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| $:=$ | Equality by definition, as opposed to a result which is $=$ |

| $S$ | Staked Ether |

| $U$ | Unstaked Ether |

| $V$ | Validator rewards, part of $U$, presumed equilibrated on $\tau$ |

| $A:=S+U$ | Circulating/Accessible Supply of Ether |

| $\cancel{O}$ | Burned Ether |

| $\alpha:=\dot{A}/A$ | Inflation (greek alpha) |

| $y$ | $\tau$-averaged Issuance yield |

| $y’:=dy/dS$ | “y prime” the derivative of the issuance yield curve |

| $\dot{X}:=dX/dt$ | Change in time of $X$, meant as a generic |

| $X^\star$ | “X star” a fixed point where $\dot{X}=0$ |

| $X^\bullet$ | “X spot” the value of $X$ at a given block; not a $\tau$-average |

| $(\ldots)^\star$ | any expression evaluated at the fixed point |

Footnotes

-

Open Zeppelin is an early icon of smart contract best practices, and continues to provide templates and auditing services in high demand. They have absolutely no connection to this post, our models, etc. and hopefully they will not sue us for using their name in a bad dynamical systems joke. ↩

-

For derivations involving differential equations,

D(used for staking Deposit) and its corresponding intensivedare cursed variables.swas already in use in some places for staking fraction, and we are resolute on keeping the intensive and its corresponding extensive the same letter.Cis a more natural choice for circulating supply, but then the three variables of most interest are something like(C,s,ς)which is masochistic in its sibilance, even for squares. We prefer “accessible” to circulating because the former implies you could access it, at some cost, while the latter sometimes implies a velocity of money. A velocity whichSand much ofUmay lack depending on dynamics: backed up unstaking queue, leveraged or looped CDPs, etc. But even if our terminology were actually superior, we’re not going to change economic jargon any time soon. ↩ -

Sometimes “dot x”

=dx/dtis used for the partial derivative ofxwith timet, which we denotex_t. The full relation isdx = x_t + x_A dA + x_s ds + x_α dαin which each partial is taken holding all the other variables constant, andx_tis used in practice to smuggle in any variability from non-dynamical variables. In principlex_Aandx_αare distinct; a quantity can depend on supply (how big ETH market cap is compared to BTC, say) and inflation independently. ↩ ↩2 -

We use moving quarterly averages, though any timescale

τsufficiently long that the erratic and fast dynamics of the base fee are integrated out, and the lags from (un)staking queues are not appreciable. As we are averaging quarterly, we set the staking, unstaking, and reward queues to zero, including their respective flows(R+Q+,Q-,I+P)in their codomain stocks(S,U,V); even if ethereum produces empty blocks, so long as the reward queue is not emptyU > 0. See also our section onI<=yS. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 -

We use domain/codomain in imprecise analogy with category theory mainly because we want to reserve “source” for an attractor, as per dynamical systems. The analogy, while inexact is not inappropriate. It is routine to implicitly use associativity to account for fibers of flows through multiple steps; “electricity from wind/nuclear/gas” even though the electrons are indistinguishable. Flows such as tx fees

U--F-->V,Øinvolve a categorical productVxØin that the smaller fractional flowsU--B-->Ømust factor through it. Similarly the staking queueV+(U-V)---R+Q+-->Sinvolves a coproduct in the domain. Whether there is content here beyond “flows correspond to injective maps between measurable sets” is unclear. None of this matters in the least for Ethereum dynamics, of course. If you’re reading it consider this an easter egg / attempt to detect a living and alert audience. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 -

Intensives expressed as fractions of flows such as

R/(I+P), instead of fractional rates of sources (likeJ/SorQ_-/S) occur when the source dynamical variable, hereV, is assumed to equilibratedV/dt=0. Then the outgoing flowsR+Kmust equal the incoming flowsI+P, so we chooseR=r(I+P). If onchain data indicates, say, $\approx70$% reinvestment of staking rewards intoStakes a lot longer than three months, we would revisit this assumption, though we do not expect our qualitative results to change re inflation and staking fraction. ↩ ↩2 -

For computer scientists

f << gis equivalent toF = O(g)if you’re more familiar with big-O notation. SpecificallyI << Smeans that the limit ofI/Sastgets very large is0. Contrast toI <= yS, which could just be a matter of coefficients. Asymptotic Notation is well-explained on wikipedia; see the bottom for Vinogradov. The art of using it to your advantage in calculations is demonstrated by Prof. Carl Bender. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 -

Our

(dlog y)/(dlog S) = 1 - pin the discouragement paper ↩ -

A non-zero

r=R/(I+P)is built into the smart contract of every Liquid Staking Provider (LSP). Here, token-holders provide Ether and receive a redeemable token (LST) that shares some staking rewards with them. This fraction of rewardsr_LSTis a lower bound onR/(I+P)at the fixed point. ↩ -

Splitting the staking queue into

R + Q_+allows us to somewhat separate short-term transient behavior from long-term dynamics. Speculative investment in staking by venture capitalists and novice stakers is expected to die down eventually; either they give up or they run staking like a business where making a profit matters. Every business that wants to stay in business reinvests some portion of its profits, sor,R > 0is what matters in the long run, once most everyone who wants to stake is staking. ↩ -

The use here is related to but slightly different than the simplified use “independent of systemm size” common in thermodynamics. Specifically we use that Ether is something preserved in the flow to bound the measure of the flow by the size of its domain above and zero below, with subleading terms possible. So

B ~ U - log(1+U) - U**(1/2)is possible butB ~ U + U**2andB ~ U - U**2are out. We care most about the limitS -> A (U -> 0); see7 also21 other6 footnotes22 for14 examples16 and context. ↩ -

We can often use the dependence on

tto smuggle in any forces, like market panics, etc. that we neglected to include as dynamical variables. If we cannot add something essential this way, we must add a dynamical variable. ↩ -

Readers wishing for more detail are encouraged to use the two dimensional local stability criterion (see Prof. Steven Strogatz) to solve for the condition of eigenvalues with an imaginary part. But simulate it too! ↩

-

Regarding

B = bf(1-s)Athe burn. While slashing could believably go to zero on quarterly timescales, no burnB=0implies blocks are empty. Obviouslys=1, B=0isn’t really a functioning state for Ethereum. A better asymptotic limit would be s = 1-ε making A ~ (1/ε)**2 (that’s squared… so very big as ε is very small). Detailed treatment of the burn, staking queues using expansions in ε would be necessary here, and are among our desiderata. We anticipate the need to model churn, slashing, and burn in light of stochasticity/quantization. One can use difference equations or Ito Calculus, but a useful generic behavior of such systems is obtained in a “weak coupling” limit. Perturbations due to quantization move the dynamics away from the fixed point, apparently randomly. Yet! Somehow, the average rate of precession abouts=1-εis often given by the imaginary component of the largest eigenvalue of the simpler model. ↩ ↩2 -

A warning! Simulations are necessarily imperfect, and especially if you use

method='RK4'(Runga-Kutta) or other methods based on local approximations only, it is not hard to find simulations in which it sure as hell seems like the system has settled down into a small but positive inflation fixed point. The following is a useful sanity check for the existing issuance yield curve, obtained using Jensen’s inequality. An inflation rate α cannot persist longer than Δt, according toexp(α Δt/2) - 1 < 2y1 Δt sqrt(s_ave / A_now)wheres_aveis the average of staking fraction over Δt,A_nowis the supply at the beginning of the inflation period, andy1is 166.3/yr. ↩ -

If anything the fractional rates of slashing and burn are positive with small changes in inflation, due to either a single ETH potentially being of less real value, or stimulation of economic activity attracting more validators and higher average burn. ↩ ↩2

-

Here gamma

γexpresses the sensitivity of inflation to supply initial conditions; the partialx_Aalways holds(α,s)constant, butdA = α dtand the partials in gamma arej_Aand(bf)_A. ↩ -

Global stability involves either trajectories infinitely returning to a region of the fixed point (think comets) or a contraction map showing the system shrinking to a limit set. We won’t rule out global stability, but recommend you look first for locally stable fixed points. Assessing the stability of equilibrium zero inflation in the

(A,s,α)model is interesting but probably academic. One of the eigenvalues at any fixed point withα=0is zero, so higher-order terms matter (the fixed point is degenerate), and linear-stability analysis is insufficient: we need to care about global stability not just local. A reader imbued with mathematical athleticism and free time is encouraged to think of a Lyapunov functionл(α=0) = 0 <= л(α), and obtain a contraction mappingdл(α)/dt <= 0. ↩ -

Confusingly the movement of a dynamic variable toward/away-from a fixed point is often also called a “flow”. Terms in equations like

R,J,...could then be called “fluxes”. But you’re not confused, right? ↩ -

Smallness of sensitivities wrt intensives is not guaranteed. Certainly a large magnitude, say

(bf)_s>1cannot maintain for too long;0<bf<1afterall. Locally, a large spike in derivative(bf)_s > bfis still possible. ↩ -

Why not simply choose

B = bA, essentially as was done in this 2021 post by Elowsson? (We useSfor hisDandAfor hisS.2) Obviously if there is no unstaked Ether no one can afford tx fees. Heresis a dynamical variable, sob = B(A-S) = bf(1-s)Ais more appropriate for our model. The function B might do all kinds of complicated nonsense, but it can never go negative and it can never exceed U. ↩ -

Variable parameters that are positive fractions cannot contribute fixed-points themselves, but they can strongly influence where a fixed point is. Example: as

s -> 1, if the leading terms werebf~(1-s)andj~(1-s)**2this gives increasingly larger equilibriumAass->1. ↩