What’s This About?

This post introduces a powerful integration between the Open Games Engine (OGE) and HEVM, unlocking new efficiencies and reducing errors in modeling blochchain systems from a game theoretic perspective. We’ll walk through the benefits of this integration and address current limitations

What Is the Open Games Engine?

The Open Games Engine is a flexible, modular framework for modeling strategic interactions. Think of it as a playground where rules and incentives can be designed, simulated, and tested. Blockchains and the myriad of game theoretic problems that come with then are a very natural application domain for the Open Games Engine. And indeed, we at 20squares have used to the engine for a whole series of problems.

Its strength lies in enabling precise analysis of game-theoretic mechanisms, from simple auctions to complex governance schemes. However, current modeling workflows require a significant amount of manual code implementation, particularly when it comes to simulating smart contract logic.

What Is HEVM?

HEVM (Haskell Ethereum Virtual Machine) is a robust tool for simulating and testing Ethereum smart contracts. It enables developers to execute contract code locally, providing deep insights into behavior and potential issues, all without needing to deploy on-chain.

️ The Problem: Manual Implementation

Right now, modeling smart contracts in OGE requires developers to manually reimplement background logic, such as:

- Simulating contract interactions

- Writing mock contracts for testing purposes

- Handling low-level mechanisms like gas fees and reverts

This approach is time-consuming, error-prone, and often limits the fidelity of simulations and analysis.

The Solution: Integrating OGE with HEVM

By connecting OGE with HEVM, we create a unified pipeline where smart contracts can be:

- Simulated directly using HEVM’s accurate execution environment.

- Plugged into OGE’s game models without reimplementation, ensuring consistency and reducing errors.

This integration streamlines the process, allowing developers to focus on designing and testing mechanisms instead of reinventing the wheel.

A Leading Example: Dual Governance Project

To motivate the power of this integration, we’ll use our recent work on the Dual Governance Mechanism as a an example we refer to later in this post. (See also our blog post about this project.)

This mechanism, intended as a complement to the Lido protocol as a safety module for (w)stETH holders, relies on a series of smart contracts. In the project we did analyze game theoretic properties of this mechanism. To that end we had to implement the whole mechanism, in particular its state machine. This requires a lot of manual work. The state machine alone are around 600 lines of code.

What the OGE x HEVM integration enables is that we can directly import and test the real contracts, saving time and enhancing accuracy.

Now, in the dual governance project as well as in others there is sometimes a good reason to not use the actual implementation but instead work the specification. After all the implementation might not be following the specification but the economic analysis should be base on the intended design.

Still, with the integration available, one can in principle also combine the two approaches: One can construct tests where model based implementation are compared with the implementation based analysis. In so far as there arise differences, one can then investigate the reasons for this. This equips the analyses with a very high degree of assurance.

Intro HEVM

Before we get into the specifics of this exercise, let’s quickly recap what is HEVM, what it does, and how we’re using it.

HEVM is a project by the formal methods team at Ethereum Foundation (previously part of the dapptools project) that allows the analysis of smart contracts using symbolic execution. Implemented in Haskell, (hence the h in HEVM), it allows to load smart contracts in a virtual environement and perform symbolic execution, run some unit tests against those contracts, or even run arbitrary EVM bytecode.

Because the OGE is also written in Haskell, integrating one with the other was an obvious match, to achieve this, we rely on HEVM as a Haskell library and make use of its API to take smart contracts and load them in a virtual environement that we can carefully design for game theoretical analysis. HEVM is a great comprehentive tool that accurately models the EVM runtime and provides an easy to use interface for us to use, including infrastructure to load dependencies for contracts, rely on test-chain interactions and more.

Once a contract, and its dependencies are loaded, we can setup any number of addresses to hoist the desired testing environment. With this environment, the intended use-case is to perform symbolic execution, using Z3 as a backend, of a contract to find out if any invariants are broken by the implementation of the contract. If there isn’t, then the contract is proven correct, if there is, HEVM will tell you what values can be used to break your invariant and help you find the source of the bug.

For our purposes, once the chain’s environement is setup, we instead rely on a concrete execution model, rather than a symbolic one. This gives us the ability to send transactions to the contracts and addresses we’ve setup and monitor any changes in the state of the blockchain. It is this ability to carefully inspect the state of the chain in a controlled environement that allows the OGE to perform its own game theoretic analysis. In what’s coming we see what exactly are Open Games and how to use them with HEVM for game-theoretic analysis.

Intro Open Games

Open games are a mathematical and compositional approach to game theory, based on category theory. They provide a structured way to model and analyze interactive decision-making processes, where individual agents (players) make choices in response to their environments and other players. Unlike traditional game theory, which often focuses on isolated games with fixed boundaries, open games emphasize modularity, interconnectivity, and reusability of game components.

Key Features

The theory of Open Games provides a distinct way of approaching modelling problems. Its key features are as follows:

- Compositionality: Open games can be composed together, allowing larger and more complex games to be built from smaller, well-defined components. This modular design makes open games ideal for analyzing systems where games interact or are nested within one another.

- Bidirectional Feedback: Open games explicitly account for both the forward flow of choices (players’ strategies) and the backward flow of utility (payoffs). This bidirectionality allows for “plugging” in players and whole games into environments.

- Interfaces and Open Systems: Each open game has an interface that describes how it interacts with its surroundings. Interfaces include inputs (strategic decisions) and outputs (utilities or payoffs), ensuring the game remains open and can connect seamlessly with other games or systems.

The Open Games Engine

The core innovation behind Open Games is mathematical. But what makes it practical as a modelling tool is the fact that the theory can be more or less directly translated into a software framework.

In the past years, we have developed this engine (with support by the Ethereum Foundation). You will find install instructions on the above github page and a tutorial here.

We have also written two explanatory blog posts in the past which you can find here and here.

The Prisoners Dilemma

In the following, we will explain a simple example - the Prisoner Dilemma expressed in our language. We will purse this example further in the next section when we explain how things how the Open Games Engine can be combined with HEVM.

We will introduce the engine using the Prisoner Dilemma as a leading example.

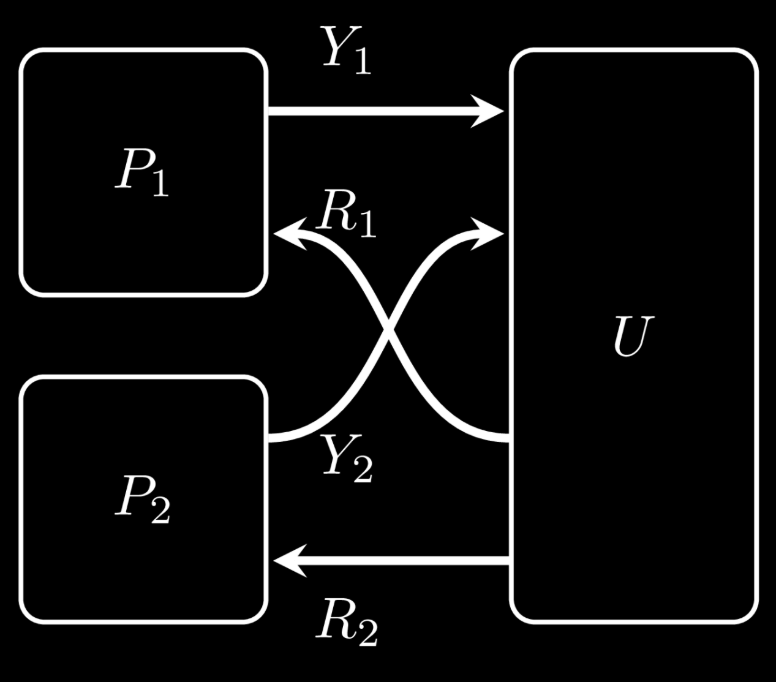

Diagrammatic representation

The theory of open games is developed within a specific category-theoretic framework that allows strategic interactions to be represented using string diagrams. These diagrams are two-dimensional, visual representations of information flow and interactions.

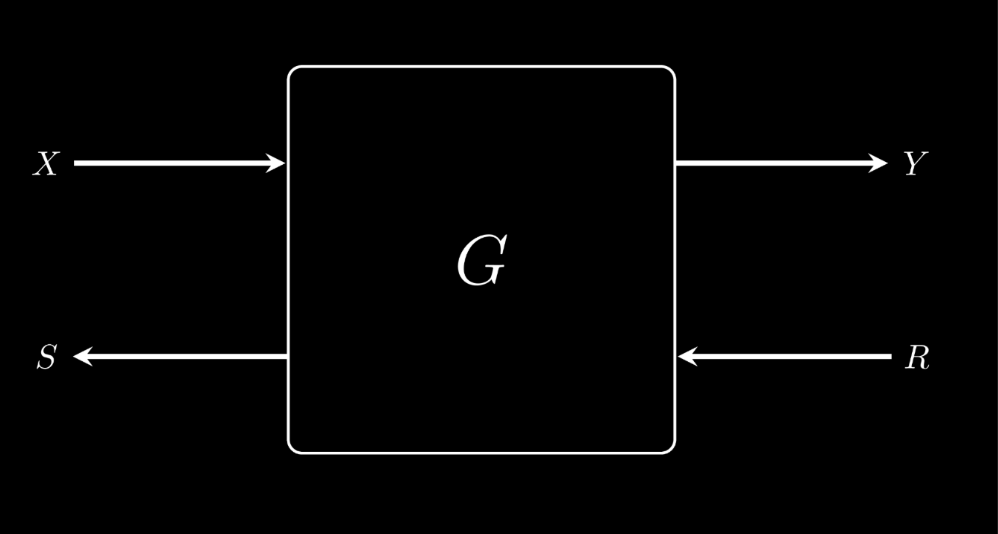

In this framework, all components of a strategic interaction are expressed as computations, which act as bidirectional information transformers. These transformers take inputs from both the left (denoted X ) and the right (denoted R ) and produce outputs in both directions: the forward flow ( Y ) and the backward flow ( S ).

At a high level, the goal of modeling with open games is to assemble these components such that the resulting structure accurately represents the intended interaction. This process is similar to “plumbing together” the flows of information, ensuring that the interconnected components reflect the strategic dynamics at play.

Here is a simple example of a simultaneous move game with two players – essentially a standard bimatrix game like the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

We will not go into the technical details behind these graphical representations here. What is important to understand at this stage is the key takeaway from the diagrams: the graphical language operates in two dimensions.

In the case of a bimatrix game, such as a simultaneous move game, Players 1 and 2 are placed side-by-side to represent that they make their decisions at the same time. However, they remain connected because each player’s utility (or payoff) is influenced not only by their own action but also by the action of the other player.

It’s worth noting that significant information is still missing from these diagrams at this point, such as:

- What are the players’ strategies?

- What are the payoffs associated with each choice?

These details are necessary to fully define the game, but for now, the diagrams serve as an intuitive way to represent the structure and interconnected nature of strategic interactions.

Types

You may wonder what restrictions exist when connecting games together. Clearly, arbitrary combinations do not make sense. The solution to this problem lies in the concept of types.

If you’re unfamiliar with types, you can think of them as tags assigned to each wire in the diagram. These tags specify what kind of object or information the wire represents. Games can only be connected if their tags match.

These tags are crucial not just for understanding the graphical representation but also for programming games. In fact, the software will automatically prevent you from connecting games with mismatched tags. If you try, the system will produce what is known as a type error.

In essence, types act as a safeguard, ensuring that only meaningful combinations of games are composed.

Syntax

The syntax for programming open games consists of two main parts:

- The outside perspective (the game as a whole).

- The internal structure (components within the game).

Let’s begin with the outside perspective.

_NameOfGame_ _var1_ _var2_ ... _varN_ = [opengame|

inputs : _InputGame_ ;

-- ^ This corresponds to X in the diagram

feedback : _FeedbackGame_ ;

-- ^ This corresponds to S in the diagram

:-------------------------:

INTERNALS OF THE GAME

:-------------------------:

output : _OutputToOutside_ ;

-- ^ This corresponds to Y in the diagram

returns : _ResultsReceivedFromOutside_ ;

-- ^ This corresponds to R in the diagram

|]

On the left-hand side:

- NameOfGame specifies the name of the game.

- var1, … , varN are optional arguments (exogenous parameters) such as utility functions, cost functions, or discount factors.

On the right-hand side:

- The

opengamesyntax contains all the relevant information to define the game. - The input/output fields represent the external interface (4 wires) of the game diagram.

- These external inputs and outputs are primarily about assigning variable names to the information that flows into and out of the game.

The internal structure of a game is defined using LineBlocks. Each LineBlock represents a modular component within the game, and the fields within it closely resemble the external input/output structure:

:-------------------------:

inputs : x ; --\

feedback : f ; \

operation : dependentDecision _playerName_ _actionSpace_ ; ==> LineBlock 1

outputs : y ; /

returns : payoffFunction x y (...) ; --/

inputs : a ; --\

... \

... ==> LineBlock 2

... /

... --/

...

:-------------------------:

Each LineBlock consists of five fields:

- inputs: Information entering this component.

- feedback: Backward flow of information.

- operation: The core computation or decision made by the component.

- outputs: Information produced as a result.

- returns: Information sent back to inform utilities or subsequent decisions.

Our goal is to model each component as a standalone open game that can be connected. The key difference between the outer and inner layers is the operation field in each LineBlock, where information is transformed or generated. A common operation is the decision operator, which models an agent choosing an action based on prior observations, an action space, and expected payoffs—typically assuming payoff maximization for simplicity.

However, in strategic situations, payoffs often depend on other players’ decisions, creating a “gap” between the decision operation and the return field. As a modeller, it’s your task to explicitly define these dependencies, while the compiler threads the required information together. This ensures clarity and modularity when modeling decisions, payoffs, and interactions within the internals of a game.

Prisoners Dilemma

Let us turn to a concrete example, the Prisoners Dilemma:

prisonersDilemma = [opengame|

inputs : ;

feedback : ;

:----------------------------:

inputs : ;

feedback : ;

operation : dependentDecision "P1" (const [Cooperate,Defect]);

outputs : y1 ;

returns : r1;

inputs : ;

feedback : ;

operation : dependentDecision "P2" (const [Cooperate,Defect]);

outputs : y2 ;

returns : r2 ;

inputs : y1,y2 ;

feedback : ;

operation : forwardFunction u

outputs : r1,r2 ;

returns : ;

:----------------------------:

outputs : ;

returns : ;

|]

In this game, there are two agents who can choose among a binary action (“Cooperate” and “Defect”). The “returns” fields for the LineBlocks of the two players reference a function prisonersDilemmaMatrix which as in the classical game representation describes the payoffs for the two players. This function depends on both players’ actions.

Note, this game has no interfacing connections to the past or the future. Which makes sense, as the Prisoner’s Dilemma is a one-shot game. In out language, it is a “closed” game.

Analytics

After representing a game, several tasks can be performed:

- Equilibrium Checking: You can verify if a given strategy tuple is an equilibrium. If it is, you receive a message like:

----Analytics begin----

Strategies are in equilibrium

NEWGAME:

----Analytics end----

If not, the output highlights profitable deviations:

—-Analytics begin—- Strategies are NOT in equilibrium. Consider the following profitable deviations:

Player: A

Optimal move: 5.0

Current Strategy: fromFreqs [(4.0,1.0)]

Optimal Payoff: 0.0

Current Payoff: -1.0

Observable State: ()

Unobservable State: "((),())

The output includes detailed information about the strategy, deviations, and payoffs.

- Parameter Exploration: If the game depends on external parameters, you can check for equilibria across a whole class of parameter values.

- Simulations: You can simulate the outcomes for a specific strategy and illustrate results, such as running simulations for particular game scenarios.

- Finding Equilibria:

You can attempt to solve the game by searching for an equilibrium. However, there are two limitations:

- Hard limitation: Computing equilibria is inherently a difficult problem.

- Current implementation: The code is not yet optimized for performance, though this may improve in the future.

In summary, you can analyze strategies, test for equilibria, run simulations, and explore solutions—while being mindful of computational challenges.

Simple example using HEVM and Open Games

Now that we have a basic grasp of Open Games and HEVM, let’s look at a simple example: The Prisoner’s dilema.

The classical way to represent this scenario is using a payoff matrix indicating the result of each pair of actions. Open games are quite well suited to those games and we can already implement them quite easily with the existing OGE, but this implementation is purely a model of something we already know. Instead, we want to analyse systems which features we don’t already know, but we know their implementation. This is how HEVM and OGE come together, we can now take an existing contract, and generate the necessary functions to perform equilibrium checking. So instead of implementing a model of the prisonner’s dilema as an Open Game, we’re going to implement a prisonner’s dilema smart contract and then check that it behaves exactly like the prisonner’s dilema we’re accustomed to.

First, we create a new prisoner.sol file with one single contract in it.

contract Prison {

address prisoner1;

address prisoner2;

bool prisoner1Defect;

bool prisoner2Defect;

bool prisoner1Played;

bool prisoner2Played;

The contract will contain the address of both participants, as well as an internal state checking who has played and what their move was.

Each player in this game has two moves, cooperate, or defect. Those functions merely record what each player’s move was and marks them as having already played.

function cooperate() public {

if (!prisoner1Played) {

prisoner1 = msg.sender;

prisoner1Defect = false;

prisoner1Played = true;

check();

} else if (!prisoner2Played) {

prisoner2 = msg.sender;

prisoner2Defect = false;

prisoner2Played = true;

check();

}

}

function defect() public {

if (!prisoner1Played) {

prisoner1 = msg.sender;

prisoner1Defect = true;

prisoner1Played = true;

check();

} else if (!prisoner2Played) {

prisoner2 = msg.sender;

prisoner2Defect = true;

prisoner2Played = true;

check();

}

}

After each move, the contract checks if the game has ended and provides the outcome to both players, this is achieved with the check function.

function check() public {

if (prisoner1Played && prisoner2Played) {

// if they both defect, they get a small prize

if (prisoner1Defect && prisoner2Defect) {

(bool res1, ) = prisoner1.call{value: 2000}("");

(bool res2, ) = prisoner2.call{value: 2000}("");

require(res1, "transfer 1 failed!");

require(res2, "transfer 2 failed!");

}

// if prisoner1 defect but prisoner2 cooperates

// prisonner1 gets a large prize and prisonner2 nothing

else if (prisoner1Defect && !prisoner2Defect) {

(bool res2, ) = prisoner1.call{value: 6000}("");

require(res2, "transfer 2 failed!");

}

// if prisoner2 defects but prisoner1 cooperates

// prisonner2 gets a large prize and prisoner1 nothing

else if (!prisoner1Defect && prisoner2Defect) {

(bool res1, ) = prisoner2.call{value: 6000}("");

require(res1, "transfer 1 failed!");

}

// if both prisoners cooperate they both get 4000

else {

(bool res1, ) = prisoner1.call{value: 4000}("");

(bool res2, ) = prisoner2.call{value: 4000}("");

require(res1, "transfer 1 failed!");

require(res2, "transfer 2 failed!");

}

}

}

As you can see, the logic of the program is quite simple, but its meaning for game theoretic analysis cannot be understated.

Once we have the smart contract written, we can import it in a Haskell file that imports OpenGames as well as the HEVM integration.

module Example.Prisoner

import EVM.TH -- import the code generator for smart contracts

import OpenGames -- import the basic tools for Open Games

import OpenGames.Engine.HEVMGames -- import the HEVM runtime for Open Games

Importing the smart contract into haskell takes just one line.

$(loadAll [mkContractFileInfo "solidity/Prisonner.sol" [mkContractInfo "Prison" "prison"]])

This says to import the Prisonner.sol contract, and bind the Prison contract to the variable prison in Haskell. This way, the API of the contract is accessible through the prison variable.

With this, we can setup the player’s addesses and some moves they can make.

player1 = LitAddr 0x1234

player2 = LitAddr 0x1235

p1defect = prison_defect player1 0 10_000_000

p2defect = prison_defect player2 0 10_000_000

p1coop = prison_cooperate player1 0 10_000_000

p2coop = prison_cooperate player2 0 10_000_000

-- each player can either cooperate or defect

optionsPlayer1 =

[ prison_defect player1 0 10_000_000,

prison_cooperate player1 0 10_000_000

]

optionsPlayer2 =

[ prison_defect player2 0 10_000_000,

prison_cooperate player2 0 10_000_000

]

Those definitions are helpers for using the functions that were generated from the smart contract itself, prison_cooperate and prison_defect are transactions with the appropriate data to send to the prison contract and call its cooperate and defect methods.

The arrays optionsPlayer1 and optionsPlayer2 are the list of move each player can make, our game theoretic model will then derive a probability distribution for them. With those we can write the main part of the game, the open game itself

hevmDilemma =

[opengame|

inputs : ;

feedback : ;

:-----------:

operation : hevmDecision "player1" optionsPlayer1 ;

outputs : decisionP1 ;

returns : balance finalState player1 ;

operation : hevmDecision "player2" optionsPlayer2 ;

outputs : decisionP2 ;

returns : balance finalState player2 ;

inputs : decisionP1, decisionP2 ;

feedback : ;

operation : fromLensM sendAndRunBoth (const pure);

outputs : finalState ;

returns : ;

:-----------:

outputs: ;

returns: ;

|]

As you can see, it is made of three parts, first, player1 choses a transaction, then player2 choses their own transaction, and once both are chosen, we send them to the contract, and extract the final state of the VM.

Running this with different strategy profiles gives us the usual outcomes: When one of the players cooperates, it’s more advantageous to defect.

----Analytics end----

----Analytics begin----

Player: player1

Optimal Move: EthTransaction {contract = LitAddr 0x1000, CALlEr = LItAddR 0x1234, METHOd = "dEfECT()", ArGuMEntS = [], ethAmt = 0x0, gas = 10000000}

Current Strategy: fromFreqs [(EthTransaction {contract = LitAddr 0x1000, callER = LITADDr 0X1234, MetHOD = "cooperATE()", ArGUmEntS = [], ethAmt = 0x0, gas = 10000000},1.0)]

Optimal Payoff: 1.000002e9

Current Payoff: 1.0e9

Observable State: ()

Unobservable State: "()"

The above output is what we get when we run equilibrium checking with both players cooperating. We see that player1 could get a higher payoff by sending a defect() transaction (this is whatOptimal Move says), but it’s currently sending a cooperate() one(we know this from Current Strategy).

With this framework, we can start experimenting with the environement just like any other open games. Create iterated games, nest multiple games within each other, add players, incentives, all while remaining faithful to what the smart contract actually do, rather than rely on what we think they do.

The code can be found here

Larger and more complex projects

If you already have an existing project that you would like to run directly within open games and perform some game-theoretic analsysis, you can leverage the foundry integration. Here is how to do it.

First compile your project with foundry using the --ast option to store the JSON ast locally. This can be done anywhere, but we suggest we do it in the root of the project. The output will be stored in the directory given by your foundry settings in foundry.toml. For example we place our contracts in contracts and the output in the out directory:

[profile.default]

out = "out"

libs = ["lib"]

ast = true

src = "contracts"

solc_version = "0.8.26"

We call foundry like expected with forge build. Once this is done, we open our opengames file, here we have a file src/Example.hs, and we use the loadFoundry quasiquote to load the output of foundry as an open game definition.

module Example

import EVM.TH

import OpenGames

import OpenGames.Engine.HEVMGames

$(loadFoundry ".")

We can use our previous example of the prisoner’s dilemma and we’d notice it works. But we can do much better. We mentioned already the Dual Governance Mechanism project before. In this case, we can load the relevant contracts by writing a wrapper contract that will import the functionality we need (from Lido), and compile it using Foundry. In contrast to the actual model we have built this saves considerable amount of code and testing.

pragma solidity ^0.8.20;

import "@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/IERC20.sol";

import "@lido-dual-governance/contracts/Escrow.sol";

contract EscrowWrapper {

Escrow public immutable escrow;

constructor(address payable _escrow) {

require(_escrow != address(0), "Invalid escrow address");

escrow = Escrow(_escrow);

}

function lockStETHAndReport(uint256 amount) external returns (uint256) {

... //implement functionality for open games here

}

}

Once this is done we can load our file and see in our REPL all the defintions we’ve generated from importing the contract:

> :l src/Example/Lido.hs

...

generating method escrowWrapper_directLockStETH

generating method escrowWrapper_getTotalLockedStETH

generating method escrowWrapper_lockStETHAndReport

generating method escrowWrapper_STETH

generating method escrowWrapper_escrow

Ok, 14 modules loaded.

This includes lockStETHAndReport which we can call through HEVM as a transaction:

-- a helper function to lock some stETH used in an open game later

stakeOrUnstakeReal = do

let lockTransaction = escrowWrapper_lockStETHAndReport(addr agent) 0 lots (fromIntegral amount)

(result, newState) <- sendAndRunAll [lockTransaction]

...

This transaction can then be part of an open game, here we use the lockStETHAndReport transaction via our helper stakeOrUnstakeReal:

// Transfer funds between staker's wallet and signalling escrow

inputs: amountStaked, globalLidoState, currentSignallingEscrowState;

feedback: ;

operation: fromLensM (\(amountStaked, globalLidoState, currentSignallingEscrowState)

-> stakeOrUnstakeReal stakingAgent amountStaked globalLidoState) (const pure);

outputs: (newGlobalLidoState, newSignallingEscrowState);

returns: ;

Of course there is a lot more modeling that is done outside of this one transaction. What we have gained is the confidence that our equilibrium checking is rooted in the reality of existing contracts and is free from translation errors. When modelling code from source, it’s easy to overlook a mistake or a specific harmless-seeming design choice made in the source code and not model it, or vice-versa, introduce errors in the model that are not in the source code. By interacting directly with the source-code via opengames, we avoid this translation step entirely, and rely on existing tools like foundry to perform the heavy lifting for us.

Links

See the README for install instructions.