First of all, happy new year! We hope you had a blast as much as we did in 2023, and that you’re all set to double down on 2024.

There seems to be a couple of new trends in the Ethereum Twitter echo chamber these days:

- The discovery that there’s MEV on Solana, and they ain’t fucking around with it;

- The fact that a lot of projects are working on parallelizing the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), and this seems to be ‘the thing’ in Ethereum now.

Clearly we can’t miss the party, and as usual we’ll try to wrtite about interesting stuff at the intersection of these topics. For starters, the natural question that we asked ourselves is:

how do you price blockspace in a parallelized world?

What is a parallelized world?

Parallel execution, in layman terms, means that you can split a given computation between different threads that happen at the same time. Thus, if you have a multi-core architecture, you can use more than one core at the same time to perform the computation. The advantage is tangible, especially given how in the last decade or so multi-core architectures have become increasingly common. Clearly, there are some tasks that are highly parallelizable - e.g. bruteforcing a password - and some tasks that aren’t - for instance computing Verifiable Delay Functions (VDFs).

A story of inclusion

Now, our idea is very simple. Parallelization is good because it makes execution faster. As such, one would like to incentivize blocks that are ‘as parallel as possible’. Furthermore, we must pair the computation layer with the economic layer, and the way we do it is via transaction fees: We put a cost on each transaction that should be proportional to how much (space, computational) resources the transaction consumes, and to how badly the user wants that transaction to be included in a block.

Naïvely, we’d like ‘highly parallelizable’ transactions to be cheaper as the amount of computation one must do is more efficient. Paradoxically, this is easier said than done, and depends on the fact that fees represent costs for some actors, but revenues for others. If we were to make ‘highly parallel transactions’ fees cheaper - e.g. by multiplying the transaction gas size by a ‘parallelization coefficient’ ranging from 0 to 1 - we would incentivize one end of the pipeline (end users, dapp developers) to push for highly parallel blocks. At the same time, we would incentivize the other end of the pipeline (the fee recipients, so validators, builders, etc) to reject highly parallel blocks in favor of sequential ones, just because they pay better.

One consequence of this is that whatever gas pricing mechanism we adopt, it cannot be too naïve. One possible way to align agents across the pipeline would be the following:

- As transaction fees, users specify gas for the ‘worst case scenario’, when the transaction is not parallelizable at all;

- At block simulation, a certain degree of parallelization is established as a function of the block;

- The users receive a discount on their fee based on this;

- The block builder instead receives the whole value of the user transaction, maybe plus a small bonus;

- The delta between what the user pays and what the builder receives is simply created, as block rewards are created now.

We are not claiming that this is the right way to do it (and indeed it’s not, because it may require to sequentially simulate the block to calculate the improvement coefficient, that defies the purpose of parallelization completely). The example above only shows how one must be a bit creative when it comes to incentive design to make sure all actors are aligned. Luckily for us, there’s a vast literature on topics such as cloud infrastructure pricing that we can boorrow from, so we don’t have to start from scratch. We will probably come up with some follow-up posts about this in the future.

A story of ordering

In the most ideal setting described above, transaction fees are taken to represent inclusion preferences. That is, you pay more depending on how badly you want to be included in a block. Unfortunately, we all know very well how the picture is much more complicated than this, as transaction fees have been (and are) used, especially in Ethereum, to represent ordering preferences, that is, how badly you want your transaction to be close to the top of the block it is in.

This observation is what ties together parallel computation and MEV. Imagine that there are two transactions that compete for being top of the block. Assume furthermore that there is no overlap whatsoever between the state read and written by them. Are the transactions ‘really’ competing? The answer is no, because the way you order them does not matter: By definition, whatever one transaction does won’t influence what the other does, and hence it doesn’t matter who ends up being on top.

This is precisely what happens in Jito, where ‘transactions that do not stomp on each other’s feet’ are put into different auctions running in parallel. This difference was highlighted in a very approachable way in Tarun’s twitter thread.

In a way, this tells us that there are MEV auctions out there that already take parallelization into account. On the surface this shouldn’t surprise, as Solana’s execution layer is already parallelized. Yet, do not let yourself be fooled by this. Indeed:

You do not need parallelized execution layers to run parallelized MEV auctions.

The knot that ties all together

So, on one hand we have parallelized execution layers, and on the other we have ‘parallelized economic layers’, if you wish. What connects these two concepts is called causality, and it is a very, very hot topic in some research areas at the moment (mainly quantum gravity and other complicated stuff, but I won’t delve into it). The whole spiel of causality is understanding and describing what does it mean for different events to be related. You can see how in a world where the notion of time changes with respect to the observer (a bit like in distributed systems), or where you can instantly teleport things around, saying ‘this event came before this one’ becomes meaningless. Instead, we want to characterize the notion of ‘causation’ in a way that is completely independent from the notion of ‘time’. If you like physics, a good, technical read about this is here.

Tarun is definitely on the right track when he points out in his thread that transactions in a Jito auction form a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). That’s one way to see it, but we have more powerful tools in our toolbox that we can use.

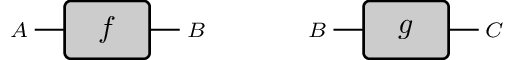

A world where only sequential composition is possible is mathematically called category. This is a term you read multiple times on this blog, but in a nutshell it means that you have processes changing state, represented as boxes:

And that processes can be piped together in the obvious way (here $g$ acts on the state changed by $f$):

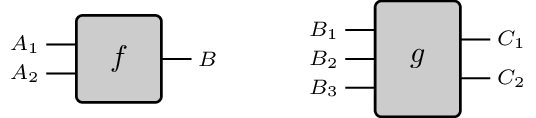

From a very high-level perspective, categories are generated by graphs, which are the underlying topologies of finite state machines. Indeed, as you will probably know, a finite state machine has just one monolithic state, which you operate on sequentially. Here causality is really boring, as ‘there is not much to do’, and the ordering between transactions is fully established. Things become much more interesting when we add another dimension, obtaining what is called a monoidal category. Here state can be split in multiple components - represented as different wires - and processes can act on different wires at the same time:

One of the main tenets of monoidal categories is the Eckmann-Hilton argument, which essentially says that ‘two processes modifying non overlapping threads have no causal relation’. Graphically, this means we can slide these processes past to each other:

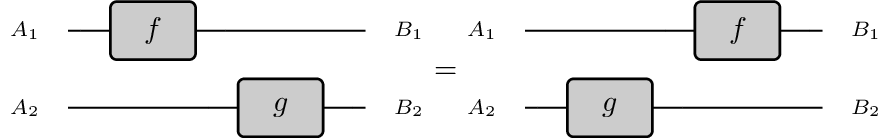

Monoidal categories in their most general form are generated by hypergraphs, which - modulo some very deep but boring caveats - are the underlying topologies of Petri nets, a very famous model of concurrent systems.

An example of how a parallel computation in a Petri net is expressed in terms of monoidal categories can be seen below from the following picture from a paper of ours:

As you can see, in the net you can fire $t$ and $u$ independently, and indeed the corresponding $t$ and $u$ processes in the ‘string diagram’ can be slid one past the other. On the other hand, you can decide if you want $v$ to use the state that was already in $p_2$ or if you want it to use the one generated by $t$ (as we do above). The two choices originate different causal structures (different DAGs in Tarun’s language) and generate different diagrams that cannot be homotopically deformed one into the other.

And so parallel computation and parallel auctions can be independent

Going back to our point, causality is what enables parallelization both at the computational and economic layer: Causally independent transactions - as $t$ and $u$ above - can be executed on different cores. Similarly, they do not compete for ordering in a block, and can be put into different auctions. But you see, these two facts are not mutually related: They are both caused by having causally-independent transactions (yes, pun intended and yes, this is higher-level causality!).

Indeed, in the (currently) non-parallel EVM we could definitely split the block not only horizontally - as in the top of the block/bottom of the block paradigm - but also vertically, allowing for multiple transactions to be top of the block and by running multiple auctions in parallel. Granted, this split only exists at ‘MEV time’ and the block will be fully sequentialized at ‘executon time’, but then again this does not matter because of the Eckmann-Hilton argument before: You can sequentialize in any ordering you want!

Obvously, in a world where:

- There are mempools, and

- Execution is parallel

Stitching the (parallel) execution and the (parallel) MEV/auction layer together becomes more important, because obviously you’d like incentives to be aligned. You don’t want block builders to cherry pick transactions in a way that reduces the usage of computational parallelism, do you? …It goes without saying that if you’re working on parallelizing the EVM and you never thought about the corresponding MEV/gas pricing mechanisms our phone lines are open!

Welcome to the Jungle

The causality story runs really deep and there are much more complex forms of causality that we already have the tools to investigate. Interesting, the parallel ‘maths - physics - models of computation - economics’ keeps holding. Just to give an example, in Physics you have teleportation, where processes can go ‘from the future to the past’, yanking the causal flow of things. The computational analogue, which is probably a bit easier to grasp, is an extension of Petri nets where you can do state borrowing and error correction. In the picture below, again taken from a paper of ours, the transition $\nu$ needs a state that hasn’t been created yet. To proceed, it creates this state together with a ‘debt’ (represented by the red token). Now $\nu$ and $\tau$ can be computed in parallel. The consistency of the whole system is restored when $\mu$ is fired, providing the state $\nu$ requested and ‘annihilating’ the debt (yes, ‘annihilation’ as in particle-antiparticle annihilation is not a coincidence here).

![]()

By ‘yanking’ the diagram, one can see that the causal flow of this computation is equivalent to firing $\tau$, then $\mu$, then $\nu$. These advanced forms of causality may be useful in intentland, where maybe we want to solve different intents ‘in parallel’ and then stitch them together afterwards.

So should you hear about ‘self-healing’ or ‘error correcting’ parallel EVM in the future, let it be know that we squatted these terms first! :P

Ok, we hope we weren’t too late to the party. Stay tuned for more updates!